I never got around to writing much about Control Room, even though I liked it quite a bit, and it's a good thing, too, because Doug Cummings has done it much better than I would have.

It's interesting to see the movie after what's happened at Abu Ghraib, which puts several scenes in a very different light.

Somehow, miraculously, someone has released Lee Chang-Dong's Oasis in theaters. It's showing this week in my town. Check yours.

I really enjoyed David Segal's review of Wilco's latest, A Ghost is Born, in today's The Washington Post. He writes:

Either Tweedy is the most generous songwriter of his generation or the stingiest. There's an emotional rawness to Ghost that implies he is giving away everything. But he's miserly with all that makes music accessible — anything that you could sing along to, for instance — even though he can create unforgettable beauty whenever, it seems, he's in the mood. The last minute of "Hummingbird," which soars on the back of a viola and hammered dulcimer, could be a missing fragment from "Abbey Road." Parts of "Company in My Back" are iridescent. So the album is like an aimless, droning lecture by a guy who every 20 minutes does a magic trick that blows your mind. You listen if only because at any moment he might start to levitate.

Wilco is moving into Radiohead territory, testing the limits of their fans who are hoping that one day the band will record another rock-n-roll record like we know they can.

But I dig the noodling.

I've been in list mode recently. It's a good way to stave off blogger guilt ("you're only as good as your last post," "people are drifting away") during a busy summer.

Recently a friend pointed me at Ymdb.com, a fun site where you can maintain a list of your 20 all-time favorite movies and view other users' lists. The site can even calculate how much affinity your list has with someone else's.

Here's my current list (circa June 2004), followed by some commentary:

2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

The Kid (Chaplin)

Rear Window (Hitchcock)

Late Spring (Ozu)

Good Men, Good Women (Hou)

The Man with the Suitcase (Akerman)

The Dekalog (Kieslowski)

The Bicycle Thief (De Sica)

The Son (Dardenne & Dardenne)

Nostalghia (Tarkovsky)

The King of Comedy (Scorsese)

Sans Soleil (Marker)

The Conversation (Coppola)

Toby Dammit (Fellini)

Nashville (Altman)

Dead Man (Jarmusch)

Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control (Morris)

Nightjohn (Burnett)

And now a few notes:

- That's only 18. Arriving at 20 movies is really, really hard. I suppose that means the list should be bursting at the seams, but by leaving a few empty slots I remind myself that it's a work in progress. Sight & Sound limits the critics and directors in its poll to ten! Rosenbaum's top 1000 sounds like a luxury by comparison. Oh, but you think that's easy?

- I followed the one-film-per-director rule.

- The list above is a snapshot of a list that's sure to change. It's something to blush about in 5 years.

- I notice that 4 or 5 of the entries are movies that I saw for the first time in the last couple of years. Maybe that means I'm being impulsive, but I hope that my life continues this way. More good movies are waiting, and a list shouldn't ossify, although I suppose a foundation would be nice.

- Earliest film: 1921 (The Kid)

- Latest film: 2002 (The Son)

- Number of silent films: one. I'm sure that Murnau's Sunrise, Lang's Metropolis, or Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc could make the list, but I've only seen one of them projected, and I only have two slots left. Math. Also omitted are Vigo's L'Atalante, Lang's M, and Dreyer's Vampyre which are early talkies but so quiet they almost seem like products of a middle era. Plus I admit that a certain contrarian streak makes me want to leave all of these staples out of the list, even though I love each one.

- Number of American films (liberal definition): a whopping nine. Number of films made in my lifetime: twelve. Clearly I could stand to broaden my selections.

- Number of films from Iran: zero. I mention this because what about Kiarostami? Or Samira Makhmalbaf? Or Jafar Panahi?

- Number of documentaries: two. But, what exactly do Sans Soleil and Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control document?

- Number of comedies: one, I suppose, The Kid, which I chose over, say, City Lights because I think it's the point at which Chaplin discovered his talent for twisting comedy and drama, second-by-second, into a single strand, and I'm not sure he ever wove them better than in the sequence where the authorities come to take his kid away. I love Keaton, too, but even a great movie like The General, which displays an elegance that Chaplin never possessed, fails to capture universal human experience the way Chaplin could.

- Well, is Toby Dammit a comedy? Yes, if comedies can remove characters' heads — and why not? — so make that two. Fellini's short is part of a crummy anthology whose English title is Spirits of the Dead. If you rent the DVD, you may skip the film by Malle, you must skip the film by Vadim, and then you have to rejigger your audio settings so that you're not listening to the English-dubbed soundtrack but instead listening to Fellini's original soundtrack, the one with Terrence Stamp's own voice. His character doesn't understand the things that are said to him in foreign languages! The hideous dubbing on the DVD flattens everything to English and completely obscures this very important joke.

- Why Nostalghia versus Stalker or Andrei Rublev or any of Tarkovsky's other films? Well, for me his movies require repeat viewings before I feel like I've gone beneath the surface, and Nostalghia is the one I've seen the most. Also, I've never seen Andrei Rublev projected, and it's hard to appreciate Tarkovsky on a TV as small as mine. Besides all that, the imagery in Nostalghia continues to amaze me.

- Number of children's movies: one, I suppose, Nightjohn. I imagine many kids would love Chaplin's movie, too, but Nightjohn was made specifically for them, by the Disney Channel, even. But that's not why it's on my list. Director Charles Burnett worked within a narrow assignment to make a movie that is honest about slavery like few movies are. When little Sarny defies the rules of her masters and learns to read, literacy seems as important as breathing. It's a profoundly moving depiction of how education empowers people and how withholding it enslaves them, which is, by the way, still true.

- Ghost Dog or Dead Man? I go back and forth, but when I think of Johnny Depp's hallucinogenic trip beyond the gates of the village at the end of the movie, I lean toward Dead Man.

- Nashville or maybe The Long Goodbye? Tough one. I need to see The Long Goodbye again.

- The Conversation or The Godfather? The Conversation. Nothing against The Godfather, but movies that feel sparse often appeal to me more than sweeping epics.

- Nothing by Claire Denis? My God, nothing by Claire Denis!

- Nothing by Jean-Luc Godard? My God, nothing by Jean-Luc Godard!

- Nothing by Carl Th. Dreyer? Sweet Mother of God, nothing by Carl Th. Dreyer!

- Or Lang? Or Hawks? Or Bresson? This is getting out of hand.

- Also nothing by Bergman, but you know there's a retrospective coming around later this year and I'll wait until I've seen more of his work on film.

Sean Spillane over at Bitter Cinema had brief but interesting entry yesterday about a web site that categorizes a few movies by theme, mostly simple themes and mostly science fiction.

The attempt to categorize by theme reminded me of Acquarello's far more thought provoking site Strictly Film School, whose theme and genre pages point not to movies but to filmmakers. The categorizations are necessarily broad, since they cover entire ouevres, but a click on one of those directors will reveal that these are no four-word film reviews.

What's interesting I think is how wide a filmmaker's scope can be even while working within an apparently constricting framework. Take Ozu, for example. His style is among the simplest of any major director, and he made the same movie over and over again — or so his critics sometimes say, derisively — using the same actors, plots, names, shots, and settings. But in a thematic breakdown like the one at Strictly Film School, Ozu falls under no less than three categories, all of them life-encompassing: "Aging/Adolescence/Death," "Generational Conflict," and "Human Condition." I think you could make the case for "Loss of Innocence/Toll of War" and "Isolation/Connection/Alienation/Ennui," too, especially as they relate to, say, aging and generational conflict.

It seems like a paradox, but by stripping his style bare Ozu seemed to bring more of the world into his grasp. A few other filmmakers — Truffaut, Tarkovsky — also cut across Acquarello's categorizations. Dewey, he of the lauded decimal system, probably would have considered this a flaw in the system. But no, I don't think so.

There's a movie in limited release in the US right now called The Five Obstructions, a collaboration between the world's oldest enfant terrible (to steal a line from Roger Ebert) Lars von Trier and his former mentor Jørgen Leth that makes this point, in a way. Not the simplicity-is-all-encompassing argument, but the bit about how limitations can be liberating.

It's true. I get the least done when my list of responsibilities and possibilities grows beyond a certain size, when it seems better just to lay on the floor and listen to the low rumble.

Coming up this week, one item on TV and the rest for folks in the Bay Area:

- Twentynine Palms — Bruno Dumont's latest movie opens at the Lumiere today, but it's already notorious, and I've been reading and reading about it for so long that I think I have to go see it, now. I've been eager to participate in discussions about the movie, assuming there's anything to say about it.

- Napoleon Dynamite — I haven't seen it, but it looks like the kind of movie that makes the people who run Landmark salivate. We get to show this? They do, starting today, at Embarcadero. Here's the trailer.

- Band of Outsiders plus Seligman — Today the PFA is showing this Godard classic and Craig Seligman will be there to introduce the movie and sign copies of his new book, which looks at the careers of Pauline Kael and Susan Sontag, especially how they approached Godard. I haven't read it, but I dig Band à part.

- Frameline 28 — Another week means another film festival, and this week it's the SF International Lesbian & Gay Film Festival. I've actually seen The Adventures of Iron Pussy, believe it or not, which the festival is showing a couple of times, and while I'm not necessarily recommending it, it's worth pointing out that it was co-directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, the Thai director whose latest film just won the Jury Prize at Cannes.

- Farmingville — This one's on TV. I may try to tune into the PBS series P.O.V., which has a lineup of interesting documentaries scheduled for the summer, starting on June 22 with Farmingville, a film about conflicts in a small New York town between long-time residents and day laborers. It could be worth a look.

I suppose the real auteur of The Adventures of Iron Pussy is Michael Shaowanasai, the writer and star who has apparently played the eponymous transvestite superspy on stage for some time, but co-director Apichatpong Weerasethakul is to blame for bringing the cinephiles to the theater. His debut feature, Mysterious Object at Noon, is a mysterious object, indeed, neither strictly a narrative nor strictly a documentary but a wandering, collaborative fantasy in the tradition of an exquisite corpse. Although it's too loose to amount to much, it signaled Weerasethakul as a creative new voice in Thai cinema. His second feature, Blissfully Yours, which I haven't seen, has a strong reputation, and his latest, Tropical Malady, polarized audiences at this year's Cannes Film Festival where it was not only the first Thai film ever to compete for the Palme d'Or but the winner of the Jury Prize, as well.

But before that he and Shaowanasai made Iron Pussy, a low-rent, PG-rated pastiche of caper movie chestnuts, musical cliches, and fabulous costumes, all captured on garish video. It doesn't sustain its initial energy level for very long, and, like most other attempts to create camp rather than discover it, the movie feels too self-aware to be very funny, but it's further evidence that Weerasethakul is a wildly unpredictable force to watch.

This week's movie log actually covers more than a week because of some recent traveling.

5-16 This So-Called Disaster (Almereyda)

5-17 What Time is it There? (Tsai) [DVD]

5-18 The Gospel According to St. Matthew (Passolini) [DVD]

5-16/20 The Office, Series One [DVD]

5-28 Distant (Ceylan)

6-04 Word Wars (Chaikin/Petrillo)

6-07 Twentieth Century (Hawks)

6-08 Melting (Andersen short)

6-08 Olivia's Place (Andersen short)

6-08 — —— (Andersen short)

6-08 Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer (Andersen)

6-09 Persona (Bergman) [DVD]

6-10 The Element of Crime (von Trier) [DVD] [half]

6-11 Saved! (Dannelly)

6-13 Los Angeles Plays Itself (Andersen)

Here are the rules, since it's been a while: all viewings are theatrical screenings unless otherwise indicated, and I don't report DVD viewings of movies I've seen before (e.g. a third of Rushmore while eating lunch).

Since Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne's movie The Son played in theaters last year, I've thought about it more than any other movie in recent memory, which seems appropriate for a work that relies so heavily on the viewer's imagination.

Much of the film's magic is in how its story unfolds, so the less said about the plot, the better. It starts simply. A man named Olivier teaches carpentry to teenage boys. He examines their work. He demonstrates proper technique. He's quiet and meticulous. Maybe this is a training program for kids who've had some trouble in their lives, but the Dardennes are far too subtle to spell that out. Instead they follow Olivier as he helps the boys measure, cut, and hammer. The camera goes where he goes and sees what he sees.

One boy in particular draws his attention. The boy has just arrived at the school, but Olivier seems to know him or know who he is, and he seems unsure about what to do when the boy wants to join his carpentry class. As the story develops, without knowing exactly why, I began to fear violence. Olivier watches the boy with a curious stare that's hard to read, and the workshop is filled with tools and heavy machines, a potentially disastrous place to be if something ugly lurks.

And that's one of the keys to The Son's power: it harnesses my own understanding — and fear — of human nature. An astounding number of movies, especially Hollywood movies, are driven by a mindless and unquestioned thirst for vengeance, but The Son looks squarely in the face of that thirst simply by observing complex human beings. It's a clear-eyed style of filmmaking reminiscent of Kieslowski's Dekalog or de Sica's neo-realist classic The Bicycle Thief, movies that adopt a raw, bare-bones aesthetic to capture the difficult morality of everyday life, where people must submit not only to the consequences of their actions but sometimes to cruel coincidence, as well.

In The Son, the boy and his teacher have histories that they bring with them to this point, but rather than explain all of that, the film merely observes what they're doing now, plunging into what feels like a very real world, knowing that these people are today the sum total of all of their days. In a characteristic scene, the boy finds pleasure in measuring parking spaces with his new ruler while admiring Olivier's ability to eyeball distances with remarkable accuracy. In another scene, a quick shot of the boy clutching his head after nearly causing an accident on a ladder says more about his mental state than ten thousand words on the subject. Simple scenes like these leave an after-image in the mind even while the movie is still going, hanging over the remainder like a canopy of leaves that layer on top of each other, giving detail to an initially barren picture. The blurry past slowly comes into focus, and yet the future remains unknown and has as much chance of being heartbreaking as it does triumphant.

And so the often claustrophobic handheld camera looks over Olivier's shoulder, literally and figuratively, as he struggles to find the right and necessary distance to keep between himself and his pupil, which is harder to eyeball than the distance between parking spaces. He, the filmmakers, and the viewers all have choices to make: what should he do, what might he do, and what's the most that a society can reasonably expect of him, knowing that people seldom reach their ideals and carry anger in their hearts?

I wanted this movie to go on observing forever, to stay immersed in this world, but it ends, abruptly, immediately after each character chooses his path. It ends, but it lingers like only the best movies linger. It's a profoundly simple, emotionally charged movie in which seldom a tear is shed, and I can't recommend it more highly.

Lars von Trier is playing a new game, but this time he's not aiming his darts at you and me. At least not directly. He's aiming them at his fellow Danish filmmaker and former mentor Jørgen Leth.

His latest project is a small movie called The Five Obstructions, and although it's his first foray into documentary filmmaking, it's not really the departure that it seems to be. This isn't the first time that he's indulged a desire to tinker with the art form, and this also isn't the first time that he's sought to bring other filmmakers into his sphere of mischief. Von Trier is one of the co-drafters of a set of rules known as "Dogma 95" which promote simplicity of filmmaking, stating that "shooting must be done on location," "optical work and filters are forbidden," and so on. The manifesto made a lot of noise when it was announced, but only one of the six films that von Trier has made since 1995 has bothered to follow its rules, prompting some to assume that it was a publicity stunt, not a real attempt to make a lasting change. That's probably true, but The Five Obstructions makes the case that a set of rules might not be such a bad thing.

One of von Trier's favorite films is a 13-minute short that Leth made in 1967 called The Perfect Human, a documentary spoof in which a clinical voice narrates banal scenes from a modern man's life — while he's eating, dancing, dressing — as if he's a wildlife specimen. "It's a little gem," von Trier tells Leth in The Five Obstructions, "which we are now going to destroy." For the documentary, von Trier asks Leth to remake the film five times, each time under a set of arbitrary rules designed by von Trier to force Leth into an uncomfortable corner.

Von Trier shows how much confidence he has in Leth by launching into a seemingly disastrous first obstruction: in the new film, no shot can be longer than half a second. You'd think that would be enough, but von Trier also stipulates that Leth cannot build any sets and must shoot the film in Cuba. "This is only the first obstruction," Leth objects. "It will be a spastic film!" But he accepts the challenge, shoots the short in Cuba, and returns to Denmark with the result. A camera crew captures the process as if it's a makeover for a TV show, which means we're privy not only to Leth's shoot, but also to von Trier's stunned reaction to the new film. In his remake, Leth uses the half-second shot clock to create an elegant, rhythmic stutter. "The limit was a gift," von Trier muses.

Always a step ahead, von Trier quickly moves past simple technical limitations and aims next for Leth's psyche, putting him in increasingly unusual situations that involve traveling to Bombay for one film and Austin, Texas, for another. After imposing the fourth obstruction, von Trier confidently says that he can't see how Leth can work within its confines to make a film that's "anything other than crap."

Leth, however, seems incapable of producing "crap," and the fantastic results that he achieves under pressure not only showcase his creative skills but also his playfulness. His strength against adversity elevates the movie above the one-sided whipping of a genial man to a more interesting duel of filmmakers. He parries when von Trier thrusts. The movie may also reveal a truth about creativity in general, that an artist's best work is often produced under tight restrictions and that the brain seems to kick in when it needs to slither around them. It's an observation that may explain why so many of von Trier's own films follow similar plot lines and yet seem stylistically diverse. The rigid skeleton remains the same, but the muscles move it through a different dance each time.

The final obstruction puts von Trier himself front and center, and some critics have been surprised by how touching it is, but it resembles a standard von Trier flourish that's beginning to look like a formula. He has a talent for whipping his audience into a misty-eyed mass in the final acts of his movies, a talent that he apparently loves to wield, especially while heaping on layers of ironic detachment that stave off any accusations of sentimentality. He wields it again in this film with a final obstruction that provides a dubious explanation for why he embarked on this project in the first place. The explanation is recorded by von Trier, spoken by Leth, and written by von Trier, as he imagines Leth should say it; as in many of his recent films, von Trier seems hopeful that if his onion has enough layers, you'll be too distracted by tears to cut too deeply.

For me, the heart of the movie isn't the sudden appearance of sweetness but the creativity of both filmmakers throughout, which I believe is rooted in a love of cinema. Von Trier's penchant for provocation and emotional manipulation often overshadows his seemingly unlimited capacity for impishness, a quality that manages to hold my attention, through all of his movies, despite an occasional desire to turn away.

Movie theaters are certainly brimming with political documentaries these days, but few of them are as sweeping in scope as The Corporation which examines the dominant institution in our society, the transnational shareholder-owned business.

The Canadian film uses for its springboard the US Constitution's 14th Amendment, which prevents states from depriving "any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." It was intended to guarantee the rights of black males, but in 1886 the Supreme Court interpreted the amendment to guarantee the rights of corporations, too.

The documentary then goes on to ask, "If corporations are legally people then what sort of people are they?" To answer that question, it marches through a laundry list of corporate misdeeds, such as lying to the public and operating sweatshops, and it solicits the comments of talking heads, many of whom are familiar to anyone who follows this debate, like Noam Chomsky and Michael Moore. Unfortunately, the few corporate defenders in the mix are used mostly as punching bags.

As a clever joke, the filmmakers run down a list of the traits of a psychopath and find a corporate action to match each one. Diagnosis: psychopath. It's cute, but it's a logical fallacy equivalent to saying that if you can find one person per symptom, then all people are psychotic. Nevertheless, while a pile of anecdotes doesn't prove anything, this pile is so high and so broad that the movie demands answers to some pretty basic questions about the economic system that we've put our faith in. As Americans, we pride ourselves on a form of government that may be imperfect but that gives representation to all citizens and defines some basic rights. At the same time, we've given increasing power to corporations that have a laser-like concentration on a very different guiding principle: increase shareholder wealth. The movie argues that it's dangerous to give so much control to an entity whose morality differs so much from our own.

Ah, the capitalist says, that shareholder wealth doesn't come out of thin air. It comes from people like you and me who do have a conscience. Therefore, you still have your say; you just say it with money. But the movie notes that a system that asks people to vote with their dollars is pretty different from a democracy because some people have far more votes than others. It's a compelling point, but the movie isn't always so insightful. When Michael Walker of the Fraser Institute defends the use of low-paying labor forces by saying that the practice applies funds to where they're needed most, the filmmakers' only rebuttal is to show the poor living conditions in third-world countries while he speaks, which doesn't fully address his point.

The hero of the movie is one of those evil CEOs himself, Ray Anderson, the head of the world's largest carpet manufacturer. A soft-spoken, self-effacing man, he tells of an epiphany that he had while reading Paul Hawken's book The Ecology of Commerce. He began to realize that his company's balance sheet didn't accurately reflect the resources that the business was taking from the earth without replenishing. But rather than leave his company in protest, he set a goal of making his company sustainable by 2020, and he's encouraged other CEOs — "fellow plunderers" — to do the same.

Lacking any clearer solution to the hydra-headed problem that it documents, the movie does well to focus on Anderson as a beacon of hope who has found a way to bridge the gap between personal responsibility and an impersonal corporation. But ironically it holds Walker up for ridicule a second time when he suggests that the solution to many of these problems is for all natural resources to be owned, an idea that's within hailing distance of what Anderson and Hawken are talking about. They may disagree on the details, but they're all seeking to use and improve — but not discard — the market system by making sure that it properly accounts for all affected resources.

Whether you agree or disagree with The Corporation's conclusions, its complaints are worthy of careful consideration. It may even encourage the warring factions to take Anderson's example and find some common ground.

Coinciding with the release of Wilco's new album is the publication of a new biography of the band by Greg Kot. Joe Klein reviews the book in the New York Times, and while the piece doesn't say much that we didn't already know, I enjoyed reading it, anyway.

Tweedy is a classic autodidact, inhaling books, constantly pushing himself to grow and change. Over time, he has become a better guitar player and learned how to mess with the computerized gimmickry of the modern recording studio. Most important, he has figured out how to sing in an entirely distinctive and compelling way. Like Dylan, Neil Young and others, Tweedy has a scratchy, nasal, good-bad voice, which depends on his emotional intelligence and phrasing, rather than timbre, for its effectiveness. His delivery is purposefully nervous, artfully irresolute. He will bend or slur a phrase, pause uncomfortably, allow a note to shatter in mid-attack; at times, it sounds as if he's very close to a nervous breakdown. There is a terrible sadness to it.

The new album is due out June 22.

Every once in a while a movie or a play or a novel contains a single nugget that sticks with you forever, a little piece of wisdom that suddenly makes sense of the world. Tom Stoppard's play Night and Day had one of those for me. I saw it performed a couple of years ago, and it always comes to mind whenever I get irked about the stuff they call "news". And it came to mind again this evening when my wife and I were talking.

The play has a lot to do with journalism, and this speech in particular struck a chord. It's a character named Jacob Milne speaking, a twenty-something journalist:

People think that rubbish-journalism is produced by men of discrimination who are vaguely ashamed of truckling to the lowest taste. But it's not. It's produced by people doing their best work. Proud of their expertise with a limited number of cheap devices to put a shine on the shit. Sorry. I know what I'm talking about because I started off like that, admiring it, trying to be that good, looking up to Fleet Street stringers, London men sometimes, on big local stories. I thought it was great. Some of the best times in my life have been spent sitting in a clapped-out Ford Consul outside a suburban house with a packet of Polos and twenty Players, waiting to grab a bereaved husband or a footballer's runaway wife who might be good for one front page between oblivion and oblivion. I felt part of a privileged group, inside society and yet outside it, with a licence to scourge it and a duty to defend it, night and day, the street of adventure, the fourth estate. And the thing is — I was dead right. That's what it was, and I was part of it because it's indivisible. Junk journalism is the evidence of a society that has got at least one thing right, that there should be nobody with the power to dictate where responsible journalism begins.

Ah, yes, back to the movies. Here are a few ideas for people in the Bay Area:

- The Corporation — Continuing at the Castro through the 17th is this epic Canadian documentary that tackles the dominant institution in our society, the transnational corporation. It's a huge amount of information, and you can't really prove something with a pile of anecdotes, but the pile is so damn high that it does provoke some fundamental questions about this system we're all a part of.

- Control Room — Jehane Noujaim's informative documentary about Al Jazeera's coverage of the war in Iraq should be required viewing, not only for the information about Al Jazeera, which is hard to come by in this country, but because it shows some of what goes on behind the scenes at military press conferences. The US military's media liason comes across as a surprisingly likable guy who's caught in the middle, convinced his side is right but not always able to empathize with the people who live in the war zone. The movie starts Friday at the Bridge.

- Since Otar Left — I think I could recommend Julie Bertuccelli's debut feature to just about anyone. Since Otar Left opens at Opera Plaza on Friday. Not only is it a warm and humorous drama, but it has a structure so subtle that it rewards consideration well after you've left the theater. Incidentally, Reverse Shot has an interesting take on the movie, reading it as an anti-Amélie, but the piece has pretty massive spoilers, so don't read it until after you see the movie.

- San Francisco Black Film Festival — Running through the 13th, the SFBFF is another of the city's many specialized festivals. The Brava theater is hosting 60 new films, many of them premieres. I haven't given the schedule a very thorough perusal, but I did notice that Girl Trouble, a documentary about San Francisco's juvenile justice system that I missed at the SFIFF, will be showing at the Bayview Opera House on Saturday afternoon.

- Los Angeles Plays Itself — You have one more chance to catch Thom Andersen's latest documentary on Sunday evening at the PFA. Not that it matters, but that's where I'll be. Also, you'll recall that the PFA is using Andersen's film as a good reason for a series of movies that highlight Los Angeles.

- Oscar-Nominated Shorts — For five days starting Thursday the 17th, the Red Vic is showing this year's Academy Award-nominated shorts. It's hard to see shorts these days, but the Red Vic is making it easy by holding onto these for so long. Doug Cummings made the case a few months ago for checking these out. They're also showing Touching the Void for three days starting Friday, in case you missed it like I did.

The Life of Brian is continuing at the Bridge, and in the non-movie list, if you're interested, Dave Chappelle is doing two shows at the Fillmore. I was expecting to see Sam Phillips at the Great American Music Hall on Wednesday, but just this minute discovered that the show was last night! I had the wrong date! I suppose my tickets are at the bottom of the will call waste bin. I could cry. By the way, her new album is fantastic, and for now it'll have to do.

The Tate Modern in London is running an Edward Hopper exhibit, and by a lucky coincidence the show opened while I was there on vacation recently. The show runs until September. If you're anywhere nearby between now and then, I highly recommend stopping by.

Hopper is best known for his painting "Nighthawks" which has become such an icon that it's been referenced countless times, by everyone from Matt Groening, who drew Homer, Chief Wiggam, and Mrs. Crabapple in Hopper's famous setting, to Tom Waits who used the painting as inspiration for the cover photo of his album Nighthawks at the Diner. A recent political cartoon in the London Times even showed a sycophantic Tony Blair serving coffee to Bush, Cheney, Powell, Rumsfeld, and Rice at a Baghdad Cafe patterned after Hopper's Phillies. The clever title of the cartoon: "Night Hawks."

But what I didn't realize before I attended the exhibit, not knowing much of anything about art, is how much Hopper has influenced several generations of filmmakers, from Alfred Hitchcock to Todd Haynes, and how much inspiration he drew from film. Hopper's stock and trade are familiar American settings as seen through a dark and ironic filter, all of which makes the event something that an American cinephile like myself can sink his teeth into.

For the exhibition, not only has the Tate pulled together dozens of Hopper's far-flung paintings — many of them from the Whitney in New York, but others from such unusual pockets as a museum in Toledo, Ohio, and the personal collections of Steve Martin and Frank Sinatra — but they've also asked Haynes to curate a film series connected to the exhibit, and he's assembled a fantastic collection of films. I found the list alone to be thought provoking:

Far From Heaven and Safe (Haynes)

The Tarnished Angels (Sirk)

Chinese Roulette (Fassbinder)

Shadow of a Doubt (Hitchcock)

Blue Velvet (Lynch)

Badlands (Malick)

The Night of the Hunter (Laughton)

Grand Opera (Benning)

Giant (Stevens)

To Kill A Mockingbird (Mulligan)

News From Home (Akerman)

films of Joseph Cornell

It's interesting that Haynes includes not only his own Far From Heaven (at the museum's request, I imagine), but a sampling of Douglas Sirk as well. In Far From Heaven, Haynes imagines what a Sirk melodrama would look like if Sirk had been free to talk about things that weren't discussed openly in 1956, and much has been written about the movie's detailed imitation of Sirk's distinctive style, especially aspects of his color films like All That Heaven Allows, from which Haynes borrows much of the plot. But Hopper is clearly another influence, and stills from Far From Heaven sit easily alongside some of Hopper's paintings, celluloid distillations of his fascinations with light and interiors. (Thanks to David Hudson at GreenCine Daily for finding a better still than what I could find online.)

Far From Heaven, Haynes, 2002

Far From Heaven, Haynes, 2002

Stairway at 48 Rue de Lille, 1906

Haynes' inclusion of a Sirk film in the series suggests that he may have inherited the Hopper influence for the film through Sirk who's known for staging actors amid household items to separate or confine them, to let their body language and positioning say more than their words, an aesthetic that would be familiar to Hopper. His color films are famously lush, but Haynes' choice for the series is Sirk's black-and-white film from 1957, The Tarnished Angels. Hopper painted in realistic color, but he used light the way black and white movies do, the way cinematographers use beams and shadows to carve shapes out of a scene and define depth, the visual hallmarks of film noir.

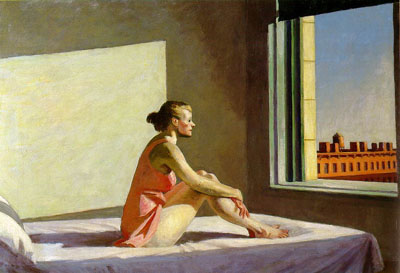

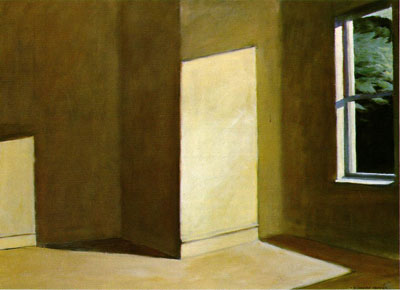

As he aged, Hopper seemed to focus more on the light itself than what it illuminated. Look at this progression of paintings in which figures are bathed in light. He shows an obvious fondness for a particular composition, but gradually the light becomes harsher and takes a more dramatic role.

In "A Woman in the Sun" a nude woman stands in a room such that every shape of her body is defined by horizontal light streaming through a window. And finally, in "Sun in an Empty Room," he removes the figure and the furniture altogether and paints the simple fact of light.

Haynes includes his earlier film Safe, too, and I've always attributed his use of geometry in that film — found in the exteriors and interiors of buildings — to an influence from Kubrick, and that's probably part of it, but Hopper fits, as well. It's not hard to imagine Kubrick himself as a fan of the painter. I don't know if he was, but he and Hopper certainly had some things in common. Like Kubrick, Hopper seemed highly meticulous, and a notebook of sketches and notes on display at the Tate bears this out. Hopper painted a world that was around the corner from Norman Rockwell's — it was the same neighborhood, and the same lovely houses, but the people in his paintings probably wouldn't have been in the real estate brochure — an attitude that seems echoed in Kubrick's recurring themes of systemic breakdown, beautiful structures that don't quite work.

In fact, while Haynes' selections have visual similarities to Hopper's work, what's most interesting is that they have a thematic kinship, as well. David Lynch's Blue Velvet takes place in a picturesque town with manicured lawns and a deep dark secret, and whether the horror beneath the pristine surface is a part of that world or wandered in from outside is never entirely clear. The same is true for the evil that lurks in Shadow of a Doubt and Night of the Hunter, where it seems to creep in through an open gate but may also be the residents' projection of things they'd prefer to keep under wraps. In several of the movies, including Badlands and Psycho (which Haynes doesn't include, although the Bates house was directly inspired by Hopper's "House by a Railroad"), people on the run from evil seem to be the agents of infection, carrying it with them wherever they roam but unable to see it in themselves. Their pursuers are eager to compress it into a single, easily contained package that can be chased and vilified with a pointed finger, like Boo Radley or Tom Robinson in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Psycho, Hitchcock, 1960

Hopper was never quite so explicit. His was the evil of quiet discontent. The people in his paintings are disconnected from each other, awkwardly posed, their bodies jutting in different planes, their gazes distant and empty, their conversation frozen. There's a lonely questioning in the isolated stares of his subjects, and his paintings of empty hotel rooms and street corners seem to provoke existential questions. They somehow suggest transience through their starkness. Where have the figures gone? Why have they left so little mark? Or so substantial a structure for so meager an existence? The couple in the idyllic cape cod yard playing with the dog seems to wonder why the house and the dog and the yard aren't satisfying their every need; the dark trees encroach from the rear. Even the dog is distracted.

All That Heaven Allows, Sirk, 1956

Hopper's approach reminds me of Antonioni's films from the 1960s in which architecture is imposing and the buildings are almost on an equal footing with the characters, who sometimes disappear without explanation; when they do, the landscape remains.

The films in the Tate series explore modern existence through idyllic symbols, a preoccupation that Hopper shared with not only filmmakers but also writers who were his contemporaries, such as Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, and John Cheever, writers whose work explores industrial-age malaise with a style devoid of flash, whose universes are so flat that objects in a room and simple turns of phrase seem to carry the same weight as the lone, leaning figures in Hopper's paintings.

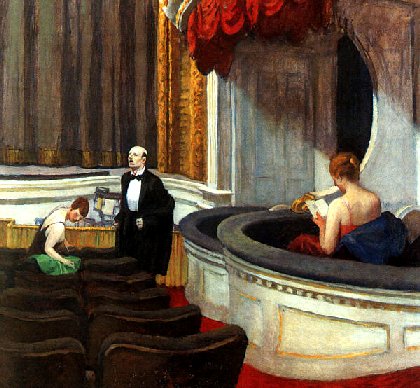

Two on the Aisle, 1927

Hopper himself was a fan of theater and the movies, and he spent a lot of time in those cavernous rooms gazing at the lighted scenes. Not surprisingly he painted their interiors, their rows of seats and isolated patrons. Also not surprisingly, he painted them nearly, but not completely, empty. I wonder if the advent of snapshots, made possible by the development of cameras that were small enough to carry around, influenced modern painters like Hopper. Who would have thought to freeze people bending and reaching in such peculiar ways before the camera began to catch them unawares?

Although I can't draw any direct lines of influence between Hopper and current Taiwanese filmmakers like Hou Hsiao-hsien and Tsai Ming-liang, I couldn't help thinking of them as I walked through the exhibit, Hou with his pools of light as thick and graspable as his characters, his frames within frames, and Tsai with his use of space, even a nearly empty movie theater in which his characters roam and try unsuccessfully to connect. Both filmmakers hold their cameras very still which makes their work easier to compare to paintings than the more kinetic films of some of their peers.

Good Men, Good Women, Hou, 1995

Goodbye, Dragon Inn, Tsai, 2003

Goodbye, Dragon Inn, Tsai, 2003

With his appropriation of cultural touchstones like signs, storefronts, and window shades, Hopper was in some ways a precursor to pop-artists like Andy Warhol (although he might dispute that), and the abstract artists Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning admired Hopper a great deal, which seems surprising until you begin to see how heavily Hopper's paintings depend on geometric patterns — rectangles of windows, trapezoids of sunlight.

Hopper's final painting shows two performers onstage taking a curtain call. The notes for the exhibit say that the figures are widely thought to be Hopper and his wife, bathed in light like so many of his subjects. It's as fitting an end to his career as I can imagine.

Two Comedians, 1966

[Haynes will discuss the film series with Richard Dyer at the Tate tomorrow, and you can watch live online. The site says an archive of the event will appear one week later.]

Compare these photos of Inger Nilsson:

I bet she still has a horse in her kitchen and walks on the walls. I can see it.

A great line from The Daily Show with Jon Stewart keeps coming to mind. A couple of weeks ago they were discussing the abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib and the rather contradictory statements from the administration about how good a job various officials are doing and how this isn't the sort of thing Americans support.

With the perfect cadence of a television reporter, faux-correspondent Rob Corddry explained it like this: "Jon, just because it's something we did doesn't mean it's something we would do."

In that same vein, I stumbled across a blog called Slacktivist in which Fred Clark comments on the president's recent appearance before a friendly group of religious journalists where he outlined his plan to spread compassion around the globe. Clark labels two of the quotations from the president's speech as a "text-book example of projection," one of which goes like this (this is Bush speaking):

I think what we're dealing with are people — extreme, radical people — who've got a deep desire to spread an ideology that is anti-women, anti-free thought, anti- art and science, you know, that couch their language in religious terms. But that doesn't make them religious people.

I also like Clark's previous post about "the dog rule" of movies. He writes:

Simply stated, the Dog Rule holds that no good movie seeks a larger emotional response from the survival of a dog than from the casual death of a dozen or more people.

He notes that several recent blockbusters have shown countless humans killed but earned points with the audience by sparing a cuddly canine.

All of this is somehow related, yes it is.