The Tate Modern in London is running an Edward Hopper exhibit, and by a lucky coincidence the show opened while I was there on vacation recently. The show runs until September. If you're anywhere nearby between now and then, I highly recommend stopping by.

Hopper is best known for his painting "Nighthawks" which has become such an icon that it's been referenced countless times, by everyone from Matt Groening, who drew Homer, Chief Wiggam, and Mrs. Crabapple in Hopper's famous setting, to Tom Waits who used the painting as inspiration for the cover photo of his album Nighthawks at the Diner. A recent political cartoon in the London Times even showed a sycophantic Tony Blair serving coffee to Bush, Cheney, Powell, Rumsfeld, and Rice at a Baghdad Cafe patterned after Hopper's Phillies. The clever title of the cartoon: "Night Hawks."

But what I didn't realize before I attended the exhibit, not knowing much of anything about art, is how much Hopper has influenced several generations of filmmakers, from Alfred Hitchcock to Todd Haynes, and how much inspiration he drew from film. Hopper's stock and trade are familiar American settings as seen through a dark and ironic filter, all of which makes the event something that an American cinephile like myself can sink his teeth into.

For the exhibition, not only has the Tate pulled together dozens of Hopper's far-flung paintings — many of them from the Whitney in New York, but others from such unusual pockets as a museum in Toledo, Ohio, and the personal collections of Steve Martin and Frank Sinatra — but they've also asked Haynes to curate a film series connected to the exhibit, and he's assembled a fantastic collection of films. I found the list alone to be thought provoking:

Far From Heaven and Safe (Haynes)

The Tarnished Angels (Sirk)

Chinese Roulette (Fassbinder)

Shadow of a Doubt (Hitchcock)

Blue Velvet (Lynch)

Badlands (Malick)

The Night of the Hunter (Laughton)

Grand Opera (Benning)

Giant (Stevens)

To Kill A Mockingbird (Mulligan)

News From Home (Akerman)

films of Joseph Cornell

It's interesting that Haynes includes not only his own Far From Heaven (at the museum's request, I imagine), but a sampling of Douglas Sirk as well. In Far From Heaven, Haynes imagines what a Sirk melodrama would look like if Sirk had been free to talk about things that weren't discussed openly in 1956, and much has been written about the movie's detailed imitation of Sirk's distinctive style, especially aspects of his color films like All That Heaven Allows, from which Haynes borrows much of the plot. But Hopper is clearly another influence, and stills from Far From Heaven sit easily alongside some of Hopper's paintings, celluloid distillations of his fascinations with light and interiors. (Thanks to David Hudson at GreenCine Daily for finding a better still than what I could find online.)

Far From Heaven, Haynes, 2002

Far From Heaven, Haynes, 2002

Stairway at 48 Rue de Lille, 1906

Haynes' inclusion of a Sirk film in the series suggests that he may have inherited the Hopper influence for the film through Sirk who's known for staging actors amid household items to separate or confine them, to let their body language and positioning say more than their words, an aesthetic that would be familiar to Hopper. His color films are famously lush, but Haynes' choice for the series is Sirk's black-and-white film from 1957, The Tarnished Angels. Hopper painted in realistic color, but he used light the way black and white movies do, the way cinematographers use beams and shadows to carve shapes out of a scene and define depth, the visual hallmarks of film noir.

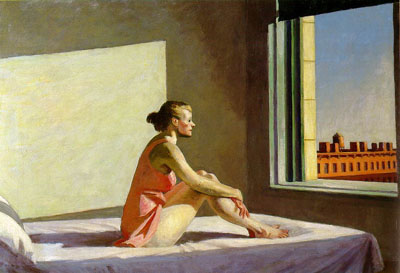

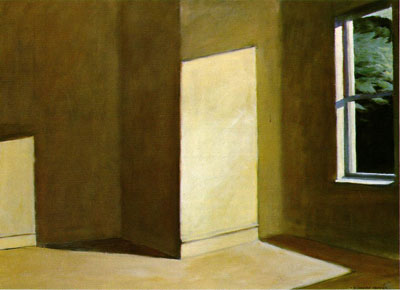

As he aged, Hopper seemed to focus more on the light itself than what it illuminated. Look at this progression of paintings in which figures are bathed in light. He shows an obvious fondness for a particular composition, but gradually the light becomes harsher and takes a more dramatic role.

In "A Woman in the Sun" a nude woman stands in a room such that every shape of her body is defined by horizontal light streaming through a window. And finally, in "Sun in an Empty Room," he removes the figure and the furniture altogether and paints the simple fact of light.

Haynes includes his earlier film Safe, too, and I've always attributed his use of geometry in that film — found in the exteriors and interiors of buildings — to an influence from Kubrick, and that's probably part of it, but Hopper fits, as well. It's not hard to imagine Kubrick himself as a fan of the painter. I don't know if he was, but he and Hopper certainly had some things in common. Like Kubrick, Hopper seemed highly meticulous, and a notebook of sketches and notes on display at the Tate bears this out. Hopper painted a world that was around the corner from Norman Rockwell's — it was the same neighborhood, and the same lovely houses, but the people in his paintings probably wouldn't have been in the real estate brochure — an attitude that seems echoed in Kubrick's recurring themes of systemic breakdown, beautiful structures that don't quite work.

In fact, while Haynes' selections have visual similarities to Hopper's work, what's most interesting is that they have a thematic kinship, as well. David Lynch's Blue Velvet takes place in a picturesque town with manicured lawns and a deep dark secret, and whether the horror beneath the pristine surface is a part of that world or wandered in from outside is never entirely clear. The same is true for the evil that lurks in Shadow of a Doubt and Night of the Hunter, where it seems to creep in through an open gate but may also be the residents' projection of things they'd prefer to keep under wraps. In several of the movies, including Badlands and Psycho (which Haynes doesn't include, although the Bates house was directly inspired by Hopper's "House by a Railroad"), people on the run from evil seem to be the agents of infection, carrying it with them wherever they roam but unable to see it in themselves. Their pursuers are eager to compress it into a single, easily contained package that can be chased and vilified with a pointed finger, like Boo Radley or Tom Robinson in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Psycho, Hitchcock, 1960

Hopper was never quite so explicit. His was the evil of quiet discontent. The people in his paintings are disconnected from each other, awkwardly posed, their bodies jutting in different planes, their gazes distant and empty, their conversation frozen. There's a lonely questioning in the isolated stares of his subjects, and his paintings of empty hotel rooms and street corners seem to provoke existential questions. They somehow suggest transience through their starkness. Where have the figures gone? Why have they left so little mark? Or so substantial a structure for so meager an existence? The couple in the idyllic cape cod yard playing with the dog seems to wonder why the house and the dog and the yard aren't satisfying their every need; the dark trees encroach from the rear. Even the dog is distracted.

All That Heaven Allows, Sirk, 1956

Hopper's approach reminds me of Antonioni's films from the 1960s in which architecture is imposing and the buildings are almost on an equal footing with the characters, who sometimes disappear without explanation; when they do, the landscape remains.

The films in the Tate series explore modern existence through idyllic symbols, a preoccupation that Hopper shared with not only filmmakers but also writers who were his contemporaries, such as Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, and John Cheever, writers whose work explores industrial-age malaise with a style devoid of flash, whose universes are so flat that objects in a room and simple turns of phrase seem to carry the same weight as the lone, leaning figures in Hopper's paintings.

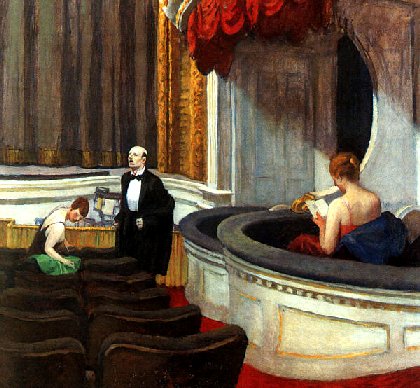

Two on the Aisle, 1927

Hopper himself was a fan of theater and the movies, and he spent a lot of time in those cavernous rooms gazing at the lighted scenes. Not surprisingly he painted their interiors, their rows of seats and isolated patrons. Also not surprisingly, he painted them nearly, but not completely, empty. I wonder if the advent of snapshots, made possible by the development of cameras that were small enough to carry around, influenced modern painters like Hopper. Who would have thought to freeze people bending and reaching in such peculiar ways before the camera began to catch them unawares?

Although I can't draw any direct lines of influence between Hopper and current Taiwanese filmmakers like Hou Hsiao-hsien and Tsai Ming-liang, I couldn't help thinking of them as I walked through the exhibit, Hou with his pools of light as thick and graspable as his characters, his frames within frames, and Tsai with his use of space, even a nearly empty movie theater in which his characters roam and try unsuccessfully to connect. Both filmmakers hold their cameras very still which makes their work easier to compare to paintings than the more kinetic films of some of their peers.

Good Men, Good Women, Hou, 1995

Goodbye, Dragon Inn, Tsai, 2003

Goodbye, Dragon Inn, Tsai, 2003

With his appropriation of cultural touchstones like signs, storefronts, and window shades, Hopper was in some ways a precursor to pop-artists like Andy Warhol (although he might dispute that), and the abstract artists Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning admired Hopper a great deal, which seems surprising until you begin to see how heavily Hopper's paintings depend on geometric patterns — rectangles of windows, trapezoids of sunlight.

Hopper's final painting shows two performers onstage taking a curtain call. The notes for the exhibit say that the figures are widely thought to be Hopper and his wife, bathed in light like so many of his subjects. It's as fitting an end to his career as I can imagine.

Two Comedians, 1966

[Haynes will discuss the film series with Richard Dyer at the Tate tomorrow, and you can watch live online. The site says an archive of the event will appear one week later.]

I came across your page as I did a google search for Hopper and Cheever. I was interested in your connection of the two, because last spring I completed a master's thesis comparing the two and exploring how each depicted the alienation of the individual left in the concrete towers of the modern city. Whereas I have always seen their works as complimentary, in researching the topic, I found almost no critical connection between the two. Although Hopper was an avid reader of the New Yorker, I couldn't find any reference to his reading Cheever. Anyway, I agree that their works work perfectly together.

sincerely,

ashby

Hey ashby, I'm glad you found your way here. That sounds like a fascinating topic for a thesis. I forgot that I mentioned Cheever in this post, but it's funny that you posted your comment this week. because I was reading some more of Cheever's stories over the holidays. The one about the radio, the one about the little girl who wanders off....

I didn't know that Hopper was a reader of the New Yorker, but it doesn't surprise me. And although there may not be any direct connections between him and Cheever (just as Taiwanese filmmakers Hou and Tsai may not be influenced at all by Hopper), I like spotting the common themes, the common ways that artists express the human condition as we're now experiencing it.

Cool.

What a fascinating post, Rob.

Have you seen the cool Todd Haynes short film "Dottie Gets Spanked"? (recently on DVD).

Its dream sequences are drawn in part from de Chirico paintings.

And I also love the many glam tableaux of "Velvet Goldmine"--so sumptuous and painterly.

Sweet mother of God, I'm delinquent in responding to posts on this site. Girish, I did, however, rent Dottie Gets Spanked at your suggestion. Haynes has always had a strong visual sense, huh? I haven't seen Velvet Goldmine, but somewhere online I found and watched his notorious Karen Carpenter biopic, Superstar. Interesting guy. I think my favorite may still be Safe.

I'm not sure I connect with the themes in Dottie but the title reminds me of Robert Coover's novella Spanking the Maid which I have to admit is a favorite of mine.

I came across your page as I did a google search for Hopper + Nighthawks. I am collecting parodies of that picture. Meanwhile I do have more than 70 pieces.

You mention one in the London Times in your article. Can you provide me with the exact issue of the London Times so I can try to buy a copy of it. Thanks

(Sorry if my English is not perfect, I am German)