In Claire Denis's Friday Night, a woman named Laure momentarily leaves a stranger in the passenger seat of her gridlocked car, and when she returns, he's behind the wheel. She climbs into the passenger seat, and for a few manic moments her car — her life — is out of her control as the man whips through alleys and side streets to circumvent the traffic jam. Laure is on the eve of moving in with her fiancé. She's reticent about the prospect, but Denis lets Laure's fear direct the camera just as it directs Laure's melancholy gaze. By catching just the right faces and turns, the camera conveys Laure's sense of possessiveness toward her car as if it's the last gasp of her vanishing freedom.

Writing about Bruno Dumont's new film Twentynine Palms in Senses of Cinema, Darren Hughes says, "when all is said and done — after the endless driving, the pain-faced orgasms, the countless miscommunications, and the brutal, brutal violence — Twentynine Palms, I think, is really a film about a red truck."

He may be right. Dumont started his filmmaking career by shooting industrial videos, and he has cited a particular shot of a candy factory — where his camera moved into a chocolate machine — as the first time he captured an emotion on video tape, an emotion triggered not by people but by twisting ribbons of dark creamy goo. It's an odd statement, but it may explain why the characters in his more recent features are so mechanical, so tactile, why their sex is so robotic, and why the red Hummer that David and Katia use for scouting photo-shoot locations in Twentynine Palms seems less like a mere conveyance and more like the outer shell of the people inside. They live at the whims of their deeply-programmed desires but are unable, or unwilling, to reconcile them where they conflict, casually stroking themselves while watching TV that they find by turns abhorrent or amazing, unable to turn away, unable to decide if ice cream tastes good or bad, unable to stop eating. But when they're in the truck, these two bundles of contradictions must move together in the same direction, and one of them needs to drive.

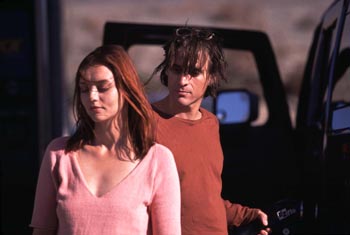

Like Laure's car in Friday Night, the red Hummer's trials and fortunes are inextricably tied to those of its occupants, and vice-versa. David and Katia get equal time on the screen, but Katia is so dramatically simple that the character seems to be David's exaggerated view of the woman, and perhaps all women: she can't drive, she's childishly indecisive, she breaks into tears when he glances at a passing woman, and she asks him if he could ever molest children. It seems clear to him that sharing this pool with her will somehow destroy him, but he plunges in headlong anyway. He's courting danger. As they drive across the Mars-like rubble, he stops the truck, jumps out, and urges Katia into the driver's seat as he jogs around to the other side. He's as game, as willfully careless, as Laure when she lets a stranger into her passenger seat, but he goes a step further by encouraging his partner to take the wheel, something that Laure's companion did only when she wasn't looking.

Katia veers into chaparral and scrapes the truck, of course, but this is only the beginning. The truck with the double-entendre name, whose color matches Katia's hair and whose blemishes are removed with a cream similar to Katia's, gradually slips from David's control. Even when he retakes the wheel he remains within Katia's sphere. He drives past a rural house, and she leans out of the passenger window to encourage a couple of dogs to run alongside. One of them is hit. To her, David's callous response proves that he's heartless. Dumont waves his hand and miraculously solves the problem, but David files the incident away and knows that more is coming.

More is coming. Katia attracts another pack of dogs, or so it seems, more vicious than the last, and the two lose control of their truck, but in a bizarre twist of fate, contrary to David's implicit prediction, Katia was not the catalyst of the attack, not even the target. When he realizes this, his picture of himself and his world is upended. His destruction is complete in his feminization, or rather in his reluctant acceptance of Katia's view of men as he understands it. Each of the film's awkward, harshly lit sex scenes concludes with a stylized male orgasm — a man's animal-like grunts — and as the film moves toward its inevitable conflict, Dumont gradually transfers those sounds to violence.

Twentynine Palms is another in a string of recent French movies that seem to be stretching the bounds of what's filmmable. The body is no longer sacred, no longer even a reflection of a person but rather an object, a churning, jerking, oozing machine. But unlike many of their peers, Dumont and Denis seem to be working toward human discovery. Denis uses objects and bodies as windows into her characters' jealously guarded thoughts and as carefully coordinated guides through elliptical stories. And Dumont, for all of his attempts to shoot landscapes devoid of beauty, sex scenes devoid of titilation, and conversations devoid of content, and for all of his attempts to equate humans and machines, he seems to be reducing humanity not to meaninglessness but to its few essential elements — desire, fear, companionship, love, hate, and, death — and the junctures where they conflict.

Dumont's third feature is not an enjoyable movie. I'm not even sure it's a worthwhile experiment. And despite a picaresque locale that screams for such treatment, no single shot in Twentynine Palms comes close to the long shot in Humanité of a man walking briskly along a ridge, nor the shot of his car disappearing into the distance down a country road. But at the very least Dumont is interested in more than just clever games, which positions him leagues away from the likes of Gaspar Noé. In talking about his shot of the chocolate machine, that pivotal point early in his career, Dumont surmised that people are drawn to the turning gears because the machine mirrors their own thought processes. Thus, his films don't so much mechanize humans as humanize machines. He searches for people within their creations, be they trucks or relationships.