Although Chris Marker is one of my favorite filmmakers, my admiration has until recently been based entirely on one feature and one short, Sans Soleil (1983) and La Jetée (1962), respectively. He's made other movies; they're just frustratingly difficult to see. I was glad to read about a retrospective in Helsinki where they'll be showing those two films and handful of others (including Terry Gilliam's 12 Monkeys, which was inspired by La Jetée).

Yeah, great, but I'd be happier if the movies were playing in my neck of the woods. But here's a little something: if you're anywhere near the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the next couple of weeks, stop in and see Marker's latest project, a 19-minute video loop called Owls at Noon.

It's in a museum, you know, so you'll have to ignore the chatter in the gallery next door and the people strolling through your field of vision. The choice of seats is limited to the floor or the wooden bench in the middle of the room, but I have a feeling fans of Marker aren't going to mind.

Owls at Noon is not a single film but a series, what Marker describes as a "subjective journey through the 20th century," beginning with World War I. What's showing at MoMA through June 13 is the first installment, called Prelude: The Hollow Men, a meditation on T.S. Eliot's poem of the same name, written in 1925 in the wake of that war. Marker takes Eliot's evocation of a shapeless, colorless, purposeless existence and applies it to the war's stunned-silent aftermath, the lull and those that came later, as if the 20th century isn't so much defined by its wars but by the brevity of the pauses between them.

The installation consists of two video feeds, sometimes showing the same pictures, other times diverging, one showing a photograph, say, and the other showing text, either an excerpt from the poem or a paragraph of commentary. Although there are only two feeds, they're displayed on a row of eight screens with each feed driving every other screen. The ribbon of alternating pictures on a black wall is most striking when both feeds are showing a photograph but one is slowly zooming in while the other is slowly zooming out. The overall effect is of a single, multi-part, undulating image, like a long banner rippling in the wind.

Marker's commentary is unspoken; it's all on the screen as text. Spacious, ominous ambient piano fills the room — it's Toru Takemitsu's "Corona" — but it seems to fade gradually in volume over the 19 minutes. With its two feeds and multiple, duplicated screens the film strikes a balance between free-form collage and a kind of directed, forward motion. Its pace and purpose are very controlled but Marker allows you to choose where to look. In fact that's not so different from Eliot's poem itself, wildly exercising the freedom to pull lines out of justification, quote from Joseph Conrad's Hearts of Darkness, replicate nursery rhymes, and shoot fireworks for Guy Fawkes, all within a linear structure of five somber stanzas.

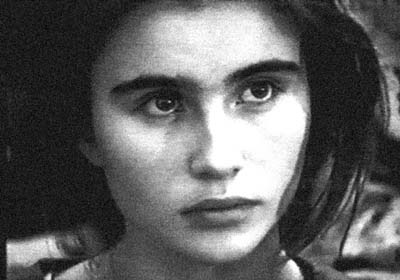

Marker's found photos underscore some of the poem's images — when Eliot writes about "eyes I dare not meet in dreams," Marker knows just the sort of eyes he means — but he's not merely illustrating the poem. With a knowledge of 20th century events that Eliot could only dread, Marker shows photo after photo of blank-faced people, hopeless and lost amid war-torn locales. To him, Eliot's "cactus land" and "fading star" might as well be barbed wire fences and military aircraft plunging toward the earth.

Always a lover of language, Marker picks up on the unusual phrases in Eliot's text, repeating "multifoliate rose" if only to highlight its strangeness and commenting on the use of "sightless," which he agrees is much better than "blind," implicitely recalling the title of his own Sans Soleil, which means not "dark" but "sunless." Some of the text in the film is so large that only a couple of letters fit at once; phrases like "HOLLOW MEN" scroll across half the screens so that from time to time the wall is filled with "HO HO HO HO" or "LO LO LO LO" or "ME ME ME ME", the frivilous syllables alternating with images of war.

Lamenting the recurring rhythm of war and the shadowy spaces between, Marker invokes this:

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

For Thine is the kingdom

That final phrase is like a non-sequitur next to the photos of destruction, or like sarcasm to call a pile of rubble and a people so empty a "kingdom." We love to build, don't we? Even more, we love to tear down, always in the name of what we've built. That's our kingdom. Or rather Thine.

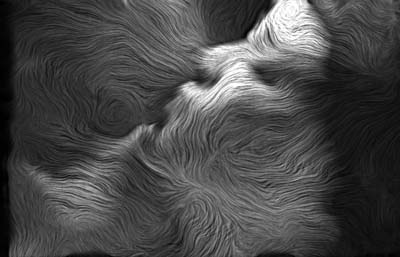

Since the film is being shown as a loop, I'm not sure where it ends and begins, but as Marker nears the end of the poem and the music grows softer, the pictures begin to decay as well. They're treated with subtle digital filters so they look old or fragmented or disintegrated. The more abstract images, like the one at the top of this post, aren't even recognizable as photographs until Marker pulls back a bit and we begin to make out the shapes.

I always like to think that the form of a video installation is somehow tied to the themes of the work, or vice-versa. I know that in most cases a museum probably just commissions this sort of thing for practical reasons — push play and let it run, no need even for a theatre. But like Shakespeare's sonnets, which all follow the exact same structure and still somehow generate a thematic thrust in sync with the dictated meter, a good video installation takes advantage of the looped exhibition.

In Owls at Noon, Marker's undulating, alternating screens, the disintegrating and reintegrating photos, the fading then reappearing musical drone, and, maybe most of all, the faces of weary people frozen the way still cameras freeze people — all of these elements live within the loop, which is woven into the theme, exemplifying Marker's concept of the poem as the prelude to a century of fleeting post-war periods.

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

Thanks for this very timely post, now I'm really glad that I had set aside an entire day to see it (since it's in a loop, maybe I'll stick around twice). Based on the furry kissing(?) picture on the MoMA site, I wasn't sure what to expect. I'm glad to see that it's still ideologically very much in keeping with Marker. It's interesting to see how much convergence there is between Marker and Harun Farocki actually, they've essentially created a post May 68 body of work that's subsumed by this idea of revolution and de(con)struction of the image. I recently had the chance to see A Grin Without a Cat for a second time, and it's still so informationally dense that it's hard to encapsulate it into anything that's even mildly coherent. Gauging by the amount of ideas being condensed in your review, I'm guessing that this will be setting off my grey cells in a tizzy. :)

Yes, I'm quite jealous that you guys get to see this; it sounds fascinating, Rob. I only saw Grin once but its informational overload still has my grey cells in a tizzy. Perhaps my most wanted film on DVD someday...

I was actually a little disappointed by the installation at first. It didn't seem quite as packed as Sans Soleil, but I liked it more after I thought about it for a while. I think the distraction of watching it in a museum gallery hurt my initial impression.

While poking around for Marker info I came across Jonathan Takagi's all-time top 11 which includes Marker's Level 5, a film I hadn't heard of. Another one for the someday list.

Contact me via email if you would like a low-quality dub of Level 5, I'd be happy to spread it around!