Chris Marker's A Grin Without a Cat

I'll be elsewhere this evening, so here are a few additional observations to wrap up the week of Last Year at Marienbad:

- The scene with the audible footsteps that I mentioned earlier ends with a voice-over explaining that after the man-who-might-be-the-woman's-husband leaves the room, the woman listens for his footsteps in the adjoining room but hears nothing. She also listens for his footsteps on the gravel below — he said he was going to the firing range — but she hears nothing there, either. Perhaps the ground is too far from the windows, the voice explains, or perhaps there's no gravel down there after all. I'm absolutely certain the footsteps on the carpet — added in post production like nearly all the sounds in the film — are intentional.

- A small bit that I love from early in the film: a woman (not Delphine Seyrig) is facing the camera. She turns to walk away, but then turns back toward the camera as if she's forgotten something, or is looking for someone, or is disoriented. And no wonder: half way through her turn, there's an edit so that by the time she's facing the camera again, her dress and surroundings have changed completely. Perhaps we're watching deja-vu.

- The man and woman are at the bar trying to recall previous events. His hand is frozen over his drink. We flash to her white bedroom, then back to the bar. Flash, then back. Repeating many times, the flashes getting longer. It's the visual equivalent of the tip of the tongue.

- The white feathery gown in which the woman is draped beautifully across the bed or shot with a gun such that she lies half on the floor like a fallen angel — I feel this image should remind me of a piece of art — is echoed in the late scenes by a black feathery gown.

- In the first scene at the firing range (which seems strangely incongruous, to be shooting pistols in this ornate room), the men fire one by one at targets. The man in the middle — the primary voice of the film — gets a close-up, and when he turns to shoot, the scene ends by cutting away to Delphine Seyrig who is walking toward the camera through a huge dark hall. But the cut is disorienting, as if he's firing a gun at the woman.

- The statue's role in the story is intriguing. The man who might be her husband, looking at a similar figure in a wall hanging, seems to offer an explanation for what it depicts: it's Charles III and his wife, the oath before the Diet, in a trial for treason; their clothing does not date from that period. Hmm. Sounds good. Except that I'm not sure what he's referring to. (Ditto the play whose title card is displayed outside the theater, Rosmer, but whose content clearly echos the film we're watching. Double ditto for the repeated half-adage "from the compass to the ship.") Nevertheless, I love the notion of a trial for treason, one of many elements of danger and betrayal that hang over the film to give card games and bedroom lights an ominous shade.

- The statue shows a man, a woman, and, facing the opposite direction, a dog. When the man and woman meet near the balustrade, he makes conversation by commenting on the statue. He interprets the scene such that the man is the primary actor; she interprets it in the other direction. She gives the figures names; he says the names don't matter and they might even be you and me, n'importe qui. But what about their dog, she asks. It's not their dog, the man explains: the dog just happened by. But why is he standing so close to her leg, she asks. Because look how small the pedestal is. (Heh, I love that.) He refers to a statue offscreen that shows the two figures without a dog. Evidence. The picture of the figures hanging in the hotel also shows no dog.

Later in the film, the man and woman are seated indoors. As usual, the man is talking. Approaching from behind is the mysterious man who may be her husband, but before he reaches them, he pauses, turns, and leaves. Who was that, the mans asks. Your husband? He just happened by, you looked right through him, and he thought it best to leave. Implication: like the dog in the statue, he does not belong to her, and indeed this hotel seems too small for the three of them.

I note with some amusement that as the man approaches from behind, his footsteps are not heard, even though he crosses rugs and a bare space between them. But the man notices his approach regardless; of course, the hotel is full of mirrors.

- I still can't figure out what we're seeing in that tracking shot down the corridor toward the mirrors, nor how it was achieved. As we move toward the mirrors, the reflected columns seem to register shadows that might belong to a camera dolly, but the vampire camera itself does not show up in the center.

- When the man tries his hand at the pyramid game one final time, having already been beaten once with cards and twice with matchsticks, he loses once more with dominos. He shrugs it off with a smile — oh well, I've lost — takes a few dominos from the pile, and lays them out in the form of a cross, like a grave marker, having been shot dead by a better marksman. He's seated; his rival is standing. Towering. Placing the dominos one by one, he keeps his hand over the last one so the cross is not obvious and probably not noticed in a casual viewing, and yet it's deliberate, because the action otherwise serves no purpose. I wonder if Resnais wanted to soften the imagery by leaving the hand there. (It works.)

- The characters in the film are never referred to by name, neither in the film nor in the credits. I sometimes see them referred to as A, X, and M, and I assume the origin is Robbe-Grillet's script, which I've not read. A man named Frank is mentioned several times, as is a Mr. Anderson who the possible husband says will be arriving in time for dinner. Could they be the same person, Mr. Anderson and Frank? (It's even possible in each ambiguous instance that Albertazzi's character, the man doing the seducing, is Frank. Someone says that Frank wasn't here last year. Another says that Frank played the pyramid game last year.) The man shows his disinterest in the woman meeting the men for dinner, referring to Anderson as Anderton or Pemberton or whoever.

- Perhaps the woman is in purgatory. Perhaps she is sick, or suicidal. If her husband had left the play early and gone to her room — to find her, to stop her — he'd still have her. But he did not, so she leaves, in black, with Death as her escort, having held him off for a year.

- Although Marienbad is normally considered a memory film, it's possible that it's not rifling through memory fragments to construct a previous event but laying out fiction fragments to construct a story. The man who tries to seduce the woman may have made up the entire thing about meeting her last year. He may be changing the story not to piece together what's been forgotten but to fit the facts — the weather, the photograph — just enough to win the girl. We can't know for sure. But, of course, his fiction relies on the very idea of faulty memories.

I've (obviously) been enjoying the new print of Last Year at Marienbad that's playing for a week in San Francisco. I once tried to imagine seeing no film but this one for the rest of my life, and Michael Smith recently remarked that he'd see every screening if it were possible. It's a dense and abstract film, and I never get tired of it. I've caught this new print twice so far and hope to duck in at least once more before the run is through, which will make this an unusual week for me. I do like to see dense movies more than once, but rarely do I have the opportunity — or desire — to see them more than twice in such a short span of time.

But this one, for me, is different. For instance, here are a few things I've noticed for the first time this week:

- There's a dude who resembles Hitchcock who can be seen in profile near the beginning, standing in the shadows on the right side of the frame, perched on one foot almost like he's hovering, or like he's a cardboard cutout.

- When the man who might be Delphine Seyrig's husband approaches the bed in her room, while she's reclining, his footsteps are clearly audible — a slow clop, clop, slide, clop — but he's walking on carpet. Of course the opening dialogue repeatedly describes carpets so thick and heavy in this old baroque hotel that the sound of no footstep reaches the ear. The speaker has a muddled memory, and we must remember that the images and sounds are no objective arbiter of the characters' conflicting recollections.

- Shot after shot after shot is a puzzle and a trick, but they come so quickly that I don't have time to work them all out. Such as: the man and the possible husband are seated at a card table, staring each other down; the camera glides past to see first them then other people playing games (including pick-up-sticks, so sophisticated), and then after gliding for a few seconds it alights once again on the man we saw at the beginning, this time walking toward us through the hallway. Or: the tracking shot down a corridor that heads straight toward a wall of shimmering mirrors... in which we of course see no camera.

- Was it Pauline Kael (I can't find a link) who remarked that the two-person pyramid game that is so closely associated with this film functions like a Western shootout. Indeed it does! And the clock chimes near the end, as we approach high noon at the OK Staircase.

- Etc. etc. etc.

I've seen Hiroshima, mon amour on this same big screen, and if I could shape the theater's calendar like clay, I'd have shown it the week before Marienbad, and then followed them up with Muriel next week, which I've only seen once (at the PFA). The actual program has Vertigo playing next week, which shows here often, but I can't complain. It's a nice way to blend the mind warp of this baroque hotel with the city in which I sit, for an entirely different sort of mind warp.

UPDATE (3/27/08): more thoughts after another viewing

Maircnhoaeflr Piistcth as Ppaauull in Michael Haneke's FFUUNNYYGGAAMMEESS.

They: You entered the Marienbad Cinema to watch Funny Games. The lobby was deserted, with hallways leading to silent offices, restrooms, concessions, the floor encrusted with the gum-like ornamentation of another age, the carpet so thick, so heavy, that no sound can be heard, as if the very ear of the moviegoer—

You: When was this?

They: 1997. Or '98.

You: It wasn't me. I have not seen it.

T: You said you had seen it.

Y: No, I have not. I've seen only the 2008 version.

T: You were there. Last year. You passed the pox office and entered the lobby—

Y: You said pox office.

T: You passed the box office and entered the lobby making no sound, as if the very ear of the person entering the pox office were—

Y: It was not me. I was not there.

T: You were! You purchased a single solitary Milk Dud and a thimble of Cherry Coke.

Y: No, always a box, always an entire box.

T: There was never a Milk Dud anyway. You entered the theater and sat watching Funny Games. It was in German.

Y: No, I did not see it. I did not see Ulrich Mühe's ankle struck by a golf club.

T: You see? You know it! You have seen it!

Y: I have not. I have only seen the 2008 version with Tim Roth.

T: Perhaps it was Ulrich Mühe and Susanne Lothar.

Y: No, it was Tim Roth and Naomi Watts.

T: Perhaps it was Mühe, perhaps it was Roth.

Y: Perhaps it was Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman.

T: Perhaps they were we. N'importe qui.

Y: And the dog?

T: It happened by. It perchance found its way onto the set.

Y: Why is it murdered in the film?

T: Because look how small the film is.

Y: No, no, I have not seen it. I've never been in here. I was out in the lobby. I was shopping. I stayed home. I was out of town. I had the chicken pox.

T: The film was projected outside of your room.

Y: In the hallway?

T: In the garden. An outdoor screening. Outside of your room.

Y: Which version?

T: Both of them.

Y: Which one came first?

T: They played at the same time.

Y: Two screens?

T: One screen. In the garden. Outside your room.

Y: Side by side? Like Jennifer Reeves: Funny Games Funny Games.

T: No, atop one another, like Michael Snow.

Y: FGUANMNEYS?

T: No, FFUUNNYYGGAAMMEESS.

Y: This did not happen, not last year. I just heard someone say that it was freezing cold outside last year. All of the screenings were cancelled. We can check the weather report in the library.

T: That's what I said. Snow.

Y: Tu est fous! Mad! Superimposing the two Funny Games!

T: You have seen them both.

Y: I have seen only one.

T: You could not have stayed in the lobby, the tromp l'oeil decor, the columns. It was empty. Everyone was seated. Everyone was watching a movie. I forget the title.

Y: Funny Games?

Michael Haneke: Where were you?

Y: Oh, hi. Umm, I was there. I was seated in the theater.

MH: I looked for you.

Y: I was in the balcony.

MH: Oh, OK. I checked the balcony.

T: There was never any balcony, anyway.

MH: It was probably just a fainting spell. Drink this. You will not die. It's not poison. The sky is not yellow. It's chicken.

Y: Pox.

T: The man who may be Michael Haneke said he had a Q&A to attend. He left your room, and you listened for the Q&A to begin in the adjoining room, but you heard nothing.

Y: Naomi Watts shoots her tormentor with a shotgun.

T: That ending will not do. I must have them alive!

Y: I presume the 1997 version is the same?

T: All of his movies are the same. But I find this one to be unique.

Y: No, they are all the same. Shh! Be quiet. He's coming.

MH: Perhaps I can be of some assistance: my violent ruffians are a pox upon us all. But you encourage them with your thoughts and deeds. You disgust me.

Y: Stop staring at They like that.

T: The man who may be Michael Haneke, whilst staring at us like that, will leave your room. He will wait outside as we discuss his film, its white interiors, its clean-cut characters. It looks simple. At first. At first.

MH: Tell me which film to play first.

Someone: The first film is always better.

Someone: The last film is always better.

Someone: Michael Haneke always wins. It's a trick of logarithms.

Someone: He plays them simultaneously for his amusement.

Someone: Michael Haneke simply knows all of the outcomes in advance.

Someone: He's a hack. Damn impressive, though.

MH: The last spectator to leave the theater loses.

Y: I have not seen the earlier one.

T: You have!

Y: Except in my head.

T: You have!

Y: When Tim Roth's ankle was struck, I saw Mühe in my head. I thought, What would this look like with Mühe instead?

T: You saw the older one in your head.

Y: I have seen only the newer one.

T: You said Mühe's performances was "ambiguous, minimally expressive".

Y: No, that was something other. I have not been to Cinema Marienbad since '97. Or '98.

MH: Tell me which one you'd like me to play first.

Someone: Play them simultaneously.

Someone: Like The Wizard of Oz and Dark Side of the Moon.

T: This story began last year. It was like some French-German co-production, with gravel and statuary and nowhere to get lost. It seemed. For me, there was nowhere to get lost. You sat in the lobby, with your mouth open as if you were about to say something, or scream, and the paper in your hand was ripped in half—

Y: By an usher.

T: Who, last year, bade you to enter.

Y: And yet I did not.

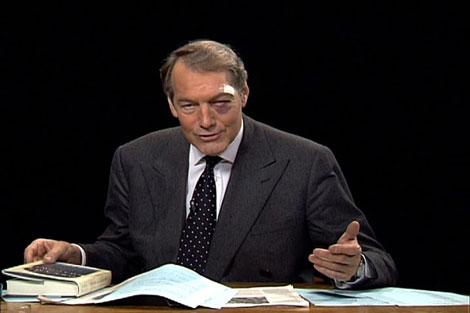

An injured Charlie Rose.

One day last week, Charlie Rose appeared on his show looking like this. He explained:

First a note about my eye. I had a little accident. I tripped and I fell on the pavement, and look what happened. And we took four of five stitches, and I'm OK. So no more questions. And I can't do that silly joke about "you should have seen the other person."

TechCrunch provided a few more details:

I contacted the show’s producers to hear what happened. Earlier today, they said, Rose tripped in a pothole while walking on 59th Street in Manhattan. He was carrying a newly purchased MacBook Air and made a quick (but ultimately flawed) decision while falling: sacrifice the face, protect the computer. "In doing so, he pretty much hit the pavement face first, unfortunately," they said.

I've had an iPhone since — ok, yes — since the week they came out. I don't talk on the phone much, but a few years ago when I needed an email-capable phone for work and started carrying a Treo, I quickly became hooked on easy access to my mail and the Internet. The Treo was fine, but the iPhone has been a welcome upgrade.

Back in September or so, I stepped out of the subway as I did every morning, iPhone in hand, headphones in ears, and began moving quickly up the escalator to exit the station. Walk left, stand right.

Half way up the escalator, in a near jog, I tripped, but without thinking I put both hands out to catch myself, which meant I slammed my iPhone between my palm and the metal escalator. I got up, dusted myself off as I rode to the top, and noticed on my left hand the grill marks from the step where I'd landed, and on my right hand nothing but a perfectly unharmed iPhone, still there, still playing, ironically, an episode of Charlie Rose. (I listen to his show often but I watch it rarely.)

My advice to anyone thinking of getting an iPhone is always the same: don't get a case. I see people carrying their phones in all sorts of sleeves and wallets and beveled bumpers designed to protect this admittedly fragile-looking piece of techno glass. But I'm here to tell you they're not necessary and that the device is much more pleasant and compact without a shell. I've dropped mine more than once, and I've slammed it hard against an escalator to protect my, you know, face. And while the thin chrome-like band that runs around the screen has a couple of minor nicks, the rest, including the touch-sensitive glass, is as pristine as the day I bought it.

I'm sure you can damage it. I do try to take good care of mine. I don't stick it in my back pocket and sit on it. Well, not often. So don't blame me if something bad happens to yours. I offer no warranties, no guarantees, just the experience of carrying an iPhone around under pretty much constant use in an urban environment with no case and, surprisingly, no ill effects.

Now, headphones ... that's another story.

Delphine Seyrig in Last Year at Marienbad by Alain Resnais

Of the movies in theaters and newly available on DVD this weekend, here's what I like, with links to my reviews, if any. I haven't seen any of the new films opening this week, although I am going to catch Drillbit Taylor. Will report back. Meanwhile ...

Jennifer Reeves' Fear of Blushing

I've been enjoying a brief retrospective of the work of New York-based experimental filmmaker Jennifer Reeves here in San Francisco. She says she wants to be the last person to leave the sinking ship that is 16mm film, and I can see why. Like many avant-garde filmmakers, she wades deep into the material by hand painting frames, placing chemicals onto the film to create colors and shapes, and otherwise manipulating her pictures in ways that aren't possible with video. Film is on its way out, and I'm amazed and excited by what's possible on video these days. See the beautiful films of Pedro Costa or Jia Zhangke or Alexander Sokurov for a few examples. But taking 16mm film from the toolbox of an artist like Reeves — every day, less of the stock is being manufactured, fewer labs are processing it, and fewer venues have equipment for showing the final product — is a little bit like telling a painter that, sorry, we won't be manufacturing canvas and oil paint in the future. Try something else. Start from scratch. With a dramatically different medium.

Reeves has begun to work with video, too, and even if it's just a hedge she's achieving some pretty amazing results. She created Light Work I by shooting video footage of her laboratory as she worked on a 16mm film called Light Work Mood Disorder. So Light Work I is like an avant-garde behind-the-scenes documentary, and although it's a video, it captures macro views of defiantly analog processes: swirling paint, cockeyed wall projection, and sewn frames of celluloid. (Michael Sicinski is the guy to read on this sort of thing, although some of what he describes are actually elements of Light Work Mood Disorder, shown second-hand in Light Work I.)

What I liked most about the San Francisco retrospective were the two venues: the first night was at the Artists' Television Access in the Mission and the other two nights were at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts downtown. The Yerba Buena screening room is a fine place for a screening, but even with your eyes closed you can feel the difference between this hermetically humming museum space and ATA's lofty, wooden storefront, where the projections are visible from the Valencia Street sidewalk. When the film starts at Yerba Buena, you'll hear some pops from the speakers as the soundtrack kicks in; at ATA, you'll hear the galloping clatter of the projectors sitting on a table at the back of the room.

That's projectors, plural. Many of Reeves' abstract works require two projectors that play two reels at once, either superimposing one frame onto another or projecting two side-by-side frames, synced up manually by Reeves so that sometimes you're seeing two independent images and sometimes you're seeing one wide image, "Light" on the left, "Work" on the right. I'm not sure which is more tangible, the cones of light above our heads or the nearly graspable patter of two machines cranking through 24 frames per second, another feature lost in the switch to video, like the incidental noise of a vinyl turntable.

Reeves originally conceived Light Work Mood Disorder for four projectors, hence the four-word title. But even an avowed fan of 16mm film occasionally bows to practicality.

I didn't bother to watch John Landis' made-for-HBO documentary about Don Rickles, which (strangely) premiered at the New York Film Festival, but I was curious about the way several news articles and a few reviews seemed delighted to discover that Rickles is actually a gentle soul with a rough exterior. ("What becomes clear in Landis' film is that Rickles is really a softie, a guy who loves humanity and life," said David Wiegand in the San Francisco Chronicle. "The guy they still call Mr. Warmth really is, and that's apparently the worst-kept secret in show business." And Marc Weingarten wrote in the New York Times, "Perhaps the most revealing insight to be gleaned from Mr. Warmth is the fact that for a man that has made a living spewing good-natured venom, Mr. Rickles is remarkably well adjusted.")

These are strange reactions because Rickles' soft side isn't a secret that's been revealed by the film; it's a decades-old part of his act, a part of the carefully crafted image that is Don Rickles. It may be genuine, too — I don't know — but his two personalities helpfully play on the natural appeal of peeking behind a performer's persona. I'm curious about this sort of thing because it's useful not only for making a crude facade more palatable but also for poking holes in an opponent's; witness the recent dust-up over comments made by Barack Obama's pastor, as if they're a window into Obama's secret hatred of America, or, more subtly, a glimpse of the calculating politician within.

My favorite piece of commentary on Rickles is also a commentary on Johnny Carson's Tonight Show, and it's a great example of satire, mostly because I'm not entirely sure how it works.

Before they were better known as Spinal Tap (or Lenny & Squiggy), Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, David Lander, and Richard Beebe performed original comedy skits on a Pasadena radio station as The Credibility Gap. "Where's Johnny" is their 1973 audio recreation of the Tonight Show, a parody so precise that it's hard to locate the edge of the knife, even as it begins to turn. Maybe it's in the unusually frank subject matter, but I think it's actually in the compression. When you boil an entire show down to just 14 minutes, the innuendo, chauvinism, homophobia, and Rickles' odd duality bubble to the top.

You can hear "Where's Johnny" free via Rhapsody (requires a quick install). Famed rock critic Robert Christgau called it "the ultimate exposé of a subject you thought didn't need it."

(And while you're at it, here is the group's authorized, rock-n-roll variation of "Who's On First," which requires Real Player. It's a hoot. Via harryshearer.com.)

Did I say there'd be a podcast this past weekend? Oh, sorry about that. I remembered that Daylight Saving Time was kicking in — I even had it marked on my calendar — but I totally forgot that we're in a leap year, so I only sprang forward an hour instead of a week, and by the time I realized everyone else had so sprung, I was totally behind on everything. Everything!

Always throws me, but I'm probably not alone, which is why I want to remind various people on whose hook I hang that come November I expect to get that week back.

Michael Haneke's Funny Games (credit: Nicole Rivelli)

Of the movies in theaters and newly available on DVD this weekend, here's what I like, with links to my reviews, if any.

Opening and Expanding This Weekend

- Funny Games — Michael Haneke remade his own film, virtually shot-for-shot, this time with Naomi Watts, Tim Roth, Michael Pitt, and Brady Corbet. He hates us, and I'm not sure what we did to provoke him.

[trailer, review (link soon)] - Snow Angels — It may be my favorite of David Gordon Green's films, although it took me some time to come to that realization. It's his most conventional in structure, but it's still an odd mix of elements.

[trailer, listen to my chat with Green on this weekend's podcast, see also: my review in the March Paste]

Gus Van Sant's Paranoid Park (credit: Scott Green)

Of the movies in theaters and newly available on DVD this weekend, here's what I like, with links to my reviews, if any. And don't forget that Daylight Saving Time goes into effect this weekend.

Opening This Weekend

Wow, the multiplex is a dead zone, but around the fringes we have:

- Paranoid Park — Gus Van Sant's latest film drifts ever so slightly back toward narrative filmmaking, which makes it easier to enjoy in the moment but maybe a little less rewarding.

[trailer, my podcast comments from New York and J. Robert's from TIFF, see also: my chat with Van Sant in the March issue of Paste Magazine (Michael Jackson's glove on the cover)] - Snow Angels — It may be my favorite of David Gordon Green's films, although it took me some time to come to that realization. It's his most conventional in structure, but it's still an odd mix of elements.

[trailer, listen to my chat with Green on this weekend's podcast, see also: my review in the March Paste] - Married Life — I resisted this period drama by Ira Sachs, trying unsuccessfully to fit it into the noir-ish or screwballsy mold that it seems to ask for, but by the end I appreciated it, mildly, as something else entirely.

[trailer, review]

At last year's San Francisco International Film Festival, after seeing Pedro Costa's Colossal Youth for a second time in eight months, Darren Hughes and I tried to put into words why we like the film so much. [Darren, I hope you don't mind my recounting a bit of this conversation from memory.]

We traded answers to that difficult question: "I didn't know a film could do that," Darren said. "I love the doorways," I said. Back and forth we went until one of us remarked that the film is so still the camera only moves twice in two and a half hours. The other concurred. Yes, only twice.

But as we talked about those two times, we realized that between us we could come up with three times that the camera moves. We both remembered the way it pivots to follow the tree-lined stream and its parallel roadway; I'd forgotten that it lowers its gaze from the treetops to watch Ventura talk about the events of 1972 and his (his?) fall from a construction site's scaffolding; and Darren hadn't noticed that the camera pans during Ventura's first apartment tour. How strange that despite our rapt attention and, by some measures, seasoned eyes, we'd each overlooked something so basic and superficial as camera movement in a film that's built almost entirely out of static shots.

So I was both startled and amused last night to discover, on my third viewing of Colossal Youth, that the camera moves five times. What the. These pans are multiplying like loaves and fishes. My God.

In order:

- In the film's first few minutes, after his wife's knifepoint monologue, Ventura enters the frame from the left and the camera pans right to follow him. This is his first appearance.

- Ventura is touring the studio apartment. It's too small. After he examines the kitchen, the camera pans right to follow him into the main room.

- After the scene in the museum, the camera points at a leafy undercarriage seen from below, then slow-spins across it and eventually brings chin to chest and finds Ventura talking with his "son."

- The camera pans left-to-right to survey a stream in a park, ticking nearly 180 degrees before it stops. Except for the cars on a roadway that runs along the stream, we don't see anyone else in the shot until a rowboat enters the settled frame and sails over our left shoulder. The camera does not follow, but we hear the paddling even after the boat is no longer visible.

- The camera pans right-to-left — counter to all the other horizontal pans — to follow Ventura and Lento into the bedroom of the burned apartment building. It pauses for the conversation at the window then pans right to follow them back to the door, which is too narrow to allow simultaneous egress.

I'm not sure if it's the film's somnolence, its rapturous compositions, its multiple axes — time, space, character, repetition, historical context, rhythm of cuts, near-narrative, fiction/non-fiction divide, trilogy completion — any one of which could be overlooked momentarily as the mind pursues a thread, limited by that old rule-of-psycho-thumb about the human brain's ability to keep only 5 or 6 items aloft simultaneously. But, whatever the reason, Colossal Youth, like most great films, releases its mysteries slowly even though it hides them in plain sight.

Last night's screening ended with a Q&A. I smiled at the first question: a woman asked Costa to comment on the film's stillness, noting that there are only two instances of movement, the post-museum dialogue and the scene at the stream. Curious. Costa, who talked at length, humbly, about the film's stillness, didn't correct her, and I'm glad about that, for the sake of the questioner and other viewers who might rather watch the paint flake on its own without any extra chiseling. The first couple of viewings are better spent on something other than counting pans.

And besides, if he'd said the camera moves seven times, I'd have heard nothing for the rest of the evening.

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Mungiu), Mobra Films/Adi Paduretu

On this edition of the podcast, we talk about our favorite films of 2007. Finally.

— Favorites of 2007, Serpentine —

0:00 Intro

2:41 Number 5

4:48 Number 4

7:04 Number 3

10:41 Number 2

12:08 Numbers 6-10

24:49 Honorable Mentions

30:12 Number 1

34:04 Favorite Screenings of Older Films

43:11 Favorite Unreleased Films

46:05 Old Filmmakers, New Filmmakers

47:51 Omissions and Irritations

58:47 Outro